Tagged: Writing

what AI can’t do

One of my favorite senitments at the moment is that ‘Hollywood is in trouble’ due to AI, with the suggestion being that AI video generators are soon going to enable a new wave of film creation, that will eventually see all kinds of regular folk building their own cinematic empires, because they can generate Hollywood level animation, or similar, with AI tools.

And definitely, AI tools are improving. Each week, there seems to be a new advance in AI video generation, and yes, at some stage, it does seem entirely feasible that you’ll be able to put together a competent, film-length project based on your idea.

But that’s the thing. Creation itself is only a part of the filmmaking journey, and it’s the writing part, in putting together a narrative that resonates with a wide audience, creating characters that work, scenes that pop, ideas that mesh, that’s not easy. And AI cannot, and will not be able to replicate that.

For example, you’ve likely seen those Pixar-style videos generated by AI tools, with people re-posting them saying things like ‘it’s so over’.

But do you know how long it takes the Pixar team to put together a story for one of their films?

Pixar generally has a team of 10 or more writers, some of the best, most experienced minds in the business, who spend several years on story development before it even gets to the storyboard/production phase.

Pixar, like all Disney projects, uses the Hero’s Journey model as its guiding light, which is a formula extrapolated from ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ monomyth structure, and is based on storytelling approaches that have been developed all throughout human existence.

And again, it takes years for them to develop these stories, using the collective experience of a team of storytellers, in order to come up with a narrative that will hit all the emotional pay-offs to maximize resonance.

AI can’t do that for you, and while AI tools may be able to help you refine a script or idea, or even streamline the conversion of your concept into actual screenplay structure, they won’t be able to polish a poor idea to the point where it’ll become a hit.

As such, even if AI tools are able to fully generate the physical elements of movie, very, very few of the ideas that get churned through these tools are actually going to gain any significant audience.

Of course, some will, and there’s no doubt that AI tools will expand opportunities for creators, by giving more people more ways to showcase their ideas in different formats. But even within that, the same rules of creation will apply, which also means that very, very few projects are going to succeed.

If you want to create resonant stories, you’re better off learning about The Hero’s Journey, and applying that to your concepts, than you would be hoping that AI tools will be able to iron out the problems with your ideas.

Most story ideas are not good, most people who think they have a cool concept for a film haven’t done the research into how to create, and it shows in the final product. I mean, even a lot of films that do make it through to production aren’t that great, and they’ve been checked and okayed by a heap of people.

So while AI tools may give you a practical means to bring your ideas to life, they won’t cover for a lack of storytelling knowledge and/or skill.

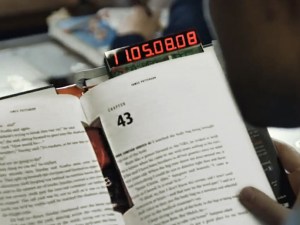

You should read this book to learn more about The Hero’s Journey in action.

lit crit

One key piece of advice that my mentor Christos Tsiolkas gave me before the publication of my first novel was this:

‘Don’t ever reply to critics’

Christos said that people are going to say what they say, and definitely, some of it is going to annoy you. But there’s no good outcome if you respond, there’s nothing you can say that hasn’t been said in the novel itself, and you’re best to just let the work have a life of its own, and be happy with what you’ve produced.

I wonder if this still applies in the modern literary landscape, where audience engagement on social media is now such a big consideration, and where publishers actually want authors to have an active presence, and be more than their work.

Because these days, who the author is matters. Where the writer came from, their life and inspirations, what they stand for, what they represent, all of these things matter more than they used to. Topicality will get you more press coverage, or at least more opportunities for interviews and discussion, while taking a definitive stance is a big part of social media resonance more broadly, due to discussion stemming from your opinions, in agreement or not, which can prompt algorithmic boosts. The modern media landscape is much more politically driven, and if you can play into that, you’ll get more coverage and awareness.

So maybe, you should respond to critics, or at least the ones who question who you are, using that as an opportunity to communicate your own stances and opinions. That could actually be a positive, but it is interesting to consider the shift in this respect.

For a lot of my favorite authors, I would have no idea who they are, beyond their work. Amy Hempel is my favorite writer, and I can’t say that I know anything much about her personal life, except that she likes dogs. Cormac McCarthy lived a fairly quiet life, though there are questionable elements of his personal history. But I have no clue what his political stances might be. I assume had he published Blood Meridian in 2025, we’d know much more about him, and that may have even tainted his legacy (if, of course, Blood Meridian would even make it to print these days).

It’s interesting to consider the shift in the way that the media handles people who come to public attention, from writers to actors and everybody else, and how we now know so much more about who they are, and what they care about, than we did in the past.

Is that a better way to approach creative talent? Do we need to know more beyond their work?

In some ways, yes. It’s good to know, for example, that J.K. Rowling has some disagreeable stances, though that does also make me a little more hesitant about supporting her work.

Is that the way that it should be, that external factors sway how we feel about their output?

Ideally, we should probably seek to judge all creative output on its merits alone, and how well the artist has expressed their vision. That would be the most pure assessment of art.

But that would also mean overlooking certain things in favor of the end result, ignoring ugly truths in favor of beautiful creations.

And that’s the way of the past, in the pre-internet era, in which predators could go unchecked for years because of their talent, and it was easier to obscure such from the public.

That’s not a good outcome either, but judging artists on anything other than the work itself also feels unfair, and could mean overlooking merit.

But in the social media era, this is more important than ever.

But if having the “wrong” opinions could kill your career, that also means that we may well be missing out on some of the best, most impactful work.

Either way, it’s another consideration in your broader literary journey, and how you maximize your opportunities.

horror fiction

I’ve been reading a bit of horror fiction of late, which I was guided towards via BookTok trends on TikTok.

TikTok is now one of the biggest influences of book sales, with trending titles getting big sales boosts, simply by catching on with the right creators.

So maybe there’s something to it, and my thought process was that maybe I could learn what people are reading, and maybe that might resonate with my own work.

I also came to horror fiction via Jeff VenderMeer’s ‘Annihilation,’ which is a book that I love. Annihilation, the novel, is very different from the movie that Alex Garland made back in 2018, and the book has a whole lot more depth and structural resonance, based on literary devices, not on CGI creatures.

I also love the way that it was crafted. VanderMeer says the idea came to him in a dream, and it definitely has that raw, unhinged creative feel to it, while also being tied back to a traditional Hero’s Journey model.

So I decided to read horror fiction, based on recommendations on TikTok and the results have been…

Well, not great.

A lot of horror stories don’t work for me because they focus on the freaky elements, and not on the story and logic behind what’s happening. You see this in horror movies as well, some weird thing happens, and rather than offering explanation and resolution, you get ‘demon possession.’ The devil possessed them so anything can happen, which is really annoying for anybody that’s looking for a complete story, and a logic within the setting of the narrative.

If demon possession covers everything from heads exploding to people flying, then where’s the tension? And if there are no constraints, then where’s the consequence? I just can’t go with it when you explain away everything as ‘unexplainable,’ because it’s too open-ended to have any emotional pay off.

And so many horror novels are just badly written. They focus on the horror elements, the gore and violence, and everything else is just cliche. The bad guys are clearly bad, because they do bad things, then they get eaten by the monster and you don’t feel anything much about it. The good people are kind and caring and infallible. To me, that’s not how you write a compelling narrative.

But it is interesting to consider from a broader literary industry perspective, with respect to what’s selling at present.

Do you know which chain is the biggest book seller in Australia right now? It’s Big W, and Big W’s book section is primarily focused on cliche-ridden pulp fiction, with limited depth and far too familiar stories.

But that’s what readers are buying, and maybe, then, that’s what writers should be looking to write, if they want to actually sell their work.

What BookTok recommendations have shown me is that cliches still work, and basic story structures still resonate. And maybe, given changes in reading habits, these are the only readers buying enough to sustain authors at present.

back to it

Okay. The time has come to write about writing once again.

Why now? Because I miss talking about writing and literary theory, and I don’t get to do it anywhere else.

In terms of published work, I’m currently in a state of semi-forced hiatus, because the publishing industry isn’t really looking for what I write.

That doesn’t mean that it’s bad, necessarily, but right now, thrillers and crime novels (and recipe books) are selling, literary fiction is not. Topical books, books with expanded social commentary, books from people of marginalized backgrounds, these are the types of things that readers, and what remains of the reading audience are seeking out.

Which is good, in many ways, in giving opportunity to a wider scope of writers. But less good for me at present.

So I don’t have anything on the horizon for publishing, but I do have several manuscripts that I’ve completed to first draft, and several ideas that I’m exploring. Indeed, I write a novel a year, because I love writing, but I’m less attached to the literary industry and the scene type stuff that draws many wannabe authors in.

Of course, if someone offered me a publishing contract, I’d take it, don’t get me wrong. But also, I’m an introvert and a quiet person, and I’m happy to not have to do the circuit. So it’s good and bad.

Though that also means making less money from my fiction work, and ideally, that would be a real career path. But it’s not a realistic one, for almost any author in Australia. The average income for a fiction writer in Australia is $18,200 per year, and that’s probably at the higher end of what most writers make for their fiction work alone. So really, it would be considered a hobby, even for the names that you recognize on the bookstore shelves.

Yet, even so, I, like many others, write for the love of it, and the need to get these stories out of my head. And things change, literary trends shift, book popularity ebbs and flows.

Maybe something I write will align with the right trend at the right time at some stage.

But as I say, I still write, I still read as much as I can, and I still like to talk about the craft of writing, and learning how to become a better writer.

So I’m gonna’ go back to writing about that.

In some ways, it feels less impactful at this stage, because if my own writing isn’t selling, what can I offer in terms of valuable writing advice? But I do know writing, and what works, in general terms, versus what doesn’t.

And hopefully, if you read along, we’ll both learn some new things.

writing and motivation

Why do you write?

This is a question that I’ve been going over in my mind in recent months as I assess where my fiction projects are at.

For context, while my first novel, which was released in 2007, sold reasonably well for a lit fic debut, and won several awards, my second, released 11 years later, did not fare as strongly, which may well be the death knell for my literary career – because if you can’t show publishers that you can generate ongoing sales, ideally to an established audience, then they have less reason to reinvest in your next project.

That’s basically where I’m at. The market has changed a lot since my debut, and the reasons why people buy and read books has also shifted, with a significant portion of book marketing now focused on the author’s story, alongside the work itself. This, of course, has always been an element, but in the age of social media, author identity is a bigger consideration, and if you’re not doing all that you can to establish an audience, based on who you are as well as what you write, you’re once again diminishing your marketing value, and thus, your prospects of being published.

But I remain confident in my work. My writing is of a publishable standard, and I’ve completed several new manuscripts. I just can’t get anyone to read them. Like at all.

Which then begs the question – why write? Why do you set out on a literary project, and what are you aiming to get from your efforts?

If it’s fame and money, then lit fic is not for you, and money has never been a major element of why I write (luckily).

Ideally, you want readers, you want to connect with an audience, and a general lack of interest in reading has definitely become more pronounced, among people that I know at least.

It used to be that people would read on the train home, or they’d squeeze in a couple of chapters, propped up on a pillow in bed, before switching out the light. Now, we have phones to soak up all those gaps in attention, which makes it harder to get anyone to commit to reading long-form fiction.

People still read, with crime fiction and thrillers, as well as books from established authors still selling reasonably well. But it feels like it’s a harder pitch to get people to commit to 250+ pages than it’s ever been, which increases the barriers to success.

So if you can’t make money, and readers aren’t overly excited to check out your new stuff, is it worth writing at all?

I don’t know, and I’ve been grappling with the concept, as I continue to work on different fiction projects and ideas over time.

It seems that we now simultaneously have more pathways into publishing than ever before, with the internet and self-publishing so prominent and readily available, while we also have fewer actual readers to reach.

Then again, you don’t need a huge audience to make it worthwhile (dependent on your aims), and maybe then, self-publishing is the way to go, just to keep things going, just to keep it moving, while ideally also helping you to build an audience and establish your own market.

Maybe that’s the path I should take – but even then, it doesn’t feel like that’s really what I want, that’s not the reason that I want to write.

So what is it? What makes you want to come up with a story and map it out and write it down and put all the pieces together and have it all complete?

For me, completion is, at least in part, the goal. I have a concept that I want to explore, I develop the characters, and I’m interested to learn more about their lives and experiences, while also refining my writing and creating a dynamic, moving story. I love doing that, I love writing and re-writing, then leaving it for a few months before checking back in, to read your own words with fresh eyes. That still excites me – and maybe that’s enough, maybe I don’t need outside recognition or acknowledgment as much as I just need that creative outlet, for my own sanity as much as anything else.

But it still feels like a bit of a let down. I spend all that time crafting something complete, something that comes together, that builds page-by-page. And no one will ever read it.

Is that enough? I’m still coming to terms with that, and considering my stance, but right now, despite my latest work, in my view, being far more advanced than my past efforts, it’s just sitting on my hard drive, gathering digital dust.

So is it worth starting something new, when no one’s interested in what you have?

For me, as a learning and development exercise, there is still value in the next project. And market trends shift, things come back around. Maybe another opportunity is coming.

Till then, I’ll keep working, and see where the next story takes me.

On alternative pathways to literary success

Could the expansion of creator tools online, and in particular via social media platforms, offer new publishing potential for a broader range of fiction authors?

I’ve had this question in mind for some time, in considering the ways in which literature is now accessed, and what might be the best way to connect with modern audiences in alignment with how they’re looking to read.

Because the truth is, readers have changed. People used to read books on trains and buses, and get through a few chapters in bed before turning in each night. But the arrival of smartphones has changed this, with everybody now glued to their devices for hours on end, which then reduces the time that they’re willing to spend with books, while concurrently increasing the value proposition that authors then need to communicate to get people to commit to engaging with longer form content.

You need to hook readers in, and the easiest way to do this is to take a topical angle, tying into a prominent discussion or trend. Then, through implicit virtue, you’re bound to get at least some readers to buy and mention your book. But without a topical hook, general fiction now struggles to gain attention, and sales traction as a result.

That’s why literary trends have changed so significantly, with thrillers and historical fiction dominating general reading trends, while literary fiction falls away. Lit fic takes more time and attention, while the faster pace of thrillers aligns better with shortening attention spans.

So what do authors do? If you don’t write within defined genre constraints, and don’t have a specific political angle for your story, how can you gain optimal attention for your work?

The truth may lie in re-imagining how you communicate, with newer, digital styles of publishing potentially providing a better fit with modern readers and their content engagement habits.

That’s why Salman Rushdie’s recent announcement that he’s publishing a new novella on Substack is interesting, with a traditional fiction superstar now looking to an alternative online publishing format to maximize his reach.

Rushdie’s planning to release his latest novella in instalments, via Substack’s newsletter platform. That could see Rushdie publishing a chapter a week, for example, which is not an entirely new concept in itself, but it is interesting given the profile that Rushdie already has, and the fact that even the big names in the field are now considering alternate pathways to audience reach.

As explained by Rushdie:

“I think that new technology always makes possible new art forms, and I think literature has not found its new form in this digital age… Whatever the new thing is that’s going to arise out of this new world, I don’t think we’ve seen it yet.

In some ways, that process is actually taking literature back to its early roots, with classic authors like Dickens and others originally publishing most of their works in serialised form, as a means to attract new readers. Now, it would be scaling things back to hold attention in the same way, with the hopes that these smaller samples of the broader work can attract new audiences – though even then, there is a question around holding reader attention, and whether such process can viably translate into a sustainable form of income through subscriber-based tools.

But I think that Rushdie’s right – literature hasn’t found its right form for modern consumers just yet.

Much of the online literary discussion these days is far less about the writing itself, and far more about the political considerations around such, leading to various debates, but too often the focus shifts away from the content itself, and onto the author and/or the topic, leaving the craft of writing, and actually creating the world of the work, as a side note. Which shouldn’t be the case, but as noted, getting people to actually engage with the work itself is more and more challenging, and in order to facilitate ongoing discussion around literature and writing, we need to find the best ways to connect with readers that will align with their behaviours, essentially making such as engaging as scrolling through non-stop social media feeds.

Nobody knows what that solution will be, but more authors are experimenting with shorter form, digitally accessible formats to maximize audience reach, while establishing community connection around your work can also facilitate more value and engagement.

These are elements that authors in times past have not had to contemplate in the same way, and it can be difficult to change your thinking around how things should work, and the importance of the relationships between publishers and authors in this respect.

But clearly, things are changing, and the authors that can change with those trends, rather than battling against them, are the only ones who stand a chance of winning out.

Otherwise, more and more debut fiction writers will simply fall away, and literary discussion will increasingly shift away from the work, and more towards tangential elements.

Because that’s what’s retaining attention, and while that’s not conducive to literary culture, habitual shifts are what they are. You either listen to that, or write for yourself, and hope that, one day, someone might, maybe, read your stuff.

narrowing interest

For all the talk about growing opportunities for creators online, it feels like modern creative outlets, like online video, are far more temporary in nature, while support for traditional arts is becoming even more finite, which limits the scope for getting things like literary works published.

We’ve seen this happen with the film industry – in the mid-nineties, there was a flood of arthouse films, which seemed to thrive alongside more mainstream faire. But as technology advanced, seeing improvements in digital downloads, home cinema systems, improved content access, etc. As this happened, audiences stopped heading to arthouse films at the same rate, and studios eventually stopped funding them as a result, which has since seen the focus shift almost entirely to blockbuster movies instead, with smaller films getting a thin lifeline from Netflix and other outlets, where success, and even broad scale awareness, is largely a crapshoot.

Now we’re in the midst of a similar shift in the literary world. With people now able to access a constant form of entertainment, and distraction, in their pocket at any time, getting people to actually commit to reading a book at all is a far bigger task than it has been previously.

People don’t need a book to read on the train home from work, or to take with them on a road trip, they don’t get through a few chapters before turning off the night light. Instead, they scroll, for hours on end, through an endless and constantly updating stream of snackable, short-form content, which quenches their desire for entertainment, education and escape, without them having to lock in for hundreds of pages.

As a result of this, the big publishing houses are getting more limited in what they publish, and while there are still some interesting titles being released, their potential for success is much lower, and the threshold for a literary career, as such, is far more limited. If you want to make it, you have to sell books, and if you don’t, you won’t be getting that next contract. Your literary career can go from celebration of publication to an abrupt and unceremonious end, very quickly, and just getting that basic awareness, getting people to even pick up our book in the first place, or just know that it exists, is a challenge.

So publishers are getting more limited. If it feels like a lot of the same thing is being published, again and again, that’s because it is, while it’s far easier for the publishing houses to get media coverage, and therefore boost awareness, for stories that touch on topical issues and themes. That’s always been the case to some degree, but now, it seems like a much bigger factor, with media interest, and social media promotion, often hinging on these additional elements.

In the end, this makes the pathway to publishing far more difficult. That’s not to say it can’t be done, there are still various examples of well-written books getting published, despite not having a topical hook or angle. But sales of literary fiction, in particular, are not strong in the AUS market, and peeling people away from their phones long enough to care about your work is a rising challenge.

So what do you do? Should you look to add more topical angles to your projects? Should you lean into what’s trending, or focus on a more specific style or genre in order to boost commercial appeal?

What’s more important – the quality of the writing itself, or the marketability of such?

I don’t know. I don’t think anybody has the answers. But it’s getting harder, and connecting with audiences, despite more avenues than ever for such, is no easy feat.

creativity in crisis

Should you be actively creating at this time?

In many ways, it seems like the perfect opportunity – people have more time on their hands due to the lockdowns, there are fewer social events to attend, etc. Yet, most people I know are not feeling overly creative, and have struggled to stay focused on fiction work and art.

Why is that?

Because creativity is inspired by our lived experiences, in what we do and see each day. Fiction writers don’t come up with an idea for a story instantaneously, it takes time – it’s various pieces and elements that rattle around inside your head until they coalesce, and the seed of a story is formed.

Right now, it’s hard to be creative because our inputs are reduced, because there are not as many things happening to us personally, which makes it more difficult to gather the various remnants and ponder their meanings and reflections.

Of course, there is a lot happening, in terms of global events. On a broader scale, its one of the busiest periods in history, but those larger scale incidents lack the immediacy required in many cases, to actual feel the emotion of small moments, to understand the scope of the details.

In essence, what I’m saying is that you shouldn’t feel bad if you’re struggling to create right now. If the words aren’t flowing, if the story is not coming together. Because without our usual connection to the broader world, it’s harder to find those small pieces that you’ll need to complete the puzzle of your story.

Writers are observationalists, we pay attention to the details and absorb moments, which we then use to build an understanding of the world, and the worlds that we subsequently create. Without fewer chances to observe, our creativity, understandably, is impacted.

So go easy on yourself, there’s a lot going on, for everyone, and if you’re not feeling it right now, it’ll come back. There’s no need to pressure yourself even further if the creativity feels a little distant.

Floating

I haven’t posted anything here in quite some time.

There is a reason for that.

More soon.

Exploding Books, Technology and the Future of Literature

Thriller writer James Patterson recently released the world’s first self-destructing book. It was a gimmick – you could buy the ‘self-destructing’ version of his latest novel, which erased itself after 24 hours, or you could wait another few days and buy it in traditional book form. Patterson’s a former ad guy, so it’s not surprising that he’d come up with something like this, a stunt closely aligned to the next generation’s affections with self-destructing and disappearing content. And while we won’t have a true gauge on how effective this promotion was for some time, it’s definitely gained Patterson a lot of attention which he’d otherwise not have received – so should other writers be considering new publishing options like this?

A Changing Conversation

We’re living in extremely interesting times, from a communications perspective. The advent of social media has changed the way we interact – people are more connected, in terms of both reach and access, than ever before. This connectivity is unprecedented – we don’t know the full effects and implications of this new world, because we’re all in the midst of living in and exploring it. But what we do know is it’s different. People’s habits are changing, audience expectations and evolving, and in this, the whole structure of arts and entertainment is shifting. What we’ve long known to be the way of things is mutating before us.

This is most obvious in publishing, newspapers being the easiest example, with print publications declining as more and more people get their daily news and information online. Books, too, are changing, with Kindles and eReaders becoming more commonplace. The flow-on effect of this is that the traditional publishing model is no longer as profitable – getting a book accepted by a major publisher has always been hard, but with an increasing amount of pressure on the bottom line, the money available for new writers is rapidly drying up. Some of those publishing losses are balanced out by lower costs – an eBook costs nowhere near as much to produce as a physical book, but the return is also diminished, because they can’t charge the same amount for a digital copy. Mostly, the result is flat, there’s really not a heap for publishers to gain from the shift to more electronic readers, but as with newspapers, where traditional outlets are getting beaten is by smaller, more agile competitors who don’t have the overheads and revenue requirements that are strangling the giants. The opportunities for new players – like self-publishers – are greater than ever – though it’s a hard path to reach any sort of significant audience.

The film industry’s facing similar challenges – with more and more films available via illegitimate means so quickly online, we’re seeing fewer arthouse films get picked up by big cinema chains. This is why you’re seeing so many big-budget Hollywood films – remakes of sequels of remakes – over and over, at the movies. Because people can’t replicate the experience of seeing those epic movies at home – advances in home cinema and larger TV screens mean we can get pretty much replicate an arthouse cinema experience in our lounge room. But we can’t do massive sound, we can’t do 3D. As such, Hollywood is taking fewer risks on smaller projects, which means less opportunity for young filmmakers coming through – in the late nineties we had low-budget debuts from Darren Aronofsky (‘Pi’) and Chris Nolan (‘Memento’) that may not have even been released in the modern cinema marketplace. Yet, those are the films that got those guys to where they are now – Aronofsky’s ‘Black Swan’ was a cinematic masterpiece, and Nolan’s now one of the biggest names in movies, fuelled by the success of his Batman trilogy. With Hollywood taking fewer risks in smaller films, we may be missing out on the next generation of great film directors, and with fewer opportunities for up and coming artists, we could, effectively, see a decline in the quality of cinema for years to come. Unless we start looking elsewhere.

The Diversification of Creation

What we have seen in the film industry is that more young artists are branching into new mediums. Where they may not have opportunities in film, more innovative and creative work is coming from platforms like YouTube, Vine and Instagram. Some of these artists have progressed from their online work to cinematic opportunities – Neill Blomkamp, the director of ‘District 9’, got his first big Hollywood break because Peter Jackson saw some of the short films he’d made in his spare time on YouTube. Josh Trank, who directed the excellent ‘Chronicle’ gained recognition through his short films posted online (including this Star Wars ‘found footage’ short). Trank is now slated to direct a new, standalone, Star Wars film, as well as the Fantastic Four reboot. The next wave of film-making talent is more diversified, spread across various mediums, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in new forms – and as these two examples highlight, there can be significant benefits to just being present and proactive, posting content to build your profile and build recognition. While what we know as the traditional progression of film creative is changing, we’re seeing greater opportunities through access to cameras and editing/creation apps – if you’re looking for the directors of tomorrow, you might be better off checking out ‘Best of Vine’ than Sundance (note: one of the films that generated the most buzz at the most recent Sundance was ‘Tangerine’, which was shot almost entirely on an iPhone).

Opportunities in Innovation

So what does this mean for publishing? Really, it means that we need to consider ways to be more innovative with what we do. Patterson’s exploding novel may seem like a pretty gimmicky gimmick, but this is where we need to be looking as the next iteration of book publishing and connecting with our audiences. People these days are seeking more immersive experiences, with websites tied into content and apps tied into social media discussions. As more movie studios tap into this and get better at a 360 degree approach to their content, that immersion will become the expectation, and that expectation will extend to other forms of entertainment media. Exploding books are one thing, as a concept that might get you a bit more attention for your next book launch, but it’s not so much the idea itself that’s interesting about Patterson’s promotion. It’s the fact that an author like Patterson is innovating that’s interesting, and it highlights the need for all authors to consider new platforms, new processes, new ways to engage readers. The opportunities are there, the mediums are available – it may be worth taking the time to consider how to best use them to communicate and connect with your audience.