non-fiction

For my day job, I write non-fiction, as the head of content for Social Media Today, which is an industry publication for digital marketers.

For a long time, I’d avoided writing for a day job, due to the concern that if I was writing all day, I wouldn’t want to write at night, on my fiction projects. But that conflict has never really been an issue, as I’ve been just as productive, if not more, since taking on a writing job.

And I do enjoy it. I like thinking about the cultural and societal impacts of evolving technologies, and how they change the way we interact, and social media is at the center of this, driving all-new trends and behaviors.

But non-fiction writing is also much different, and the approach to non-fiction requires a different mindset, where you’re less focused on cadence, and more focused on clarity.

I don’t have any hard and fast rules for how I approach journalism, just notes based on traditional journalistic structure and what I’ve learned over time.

And I write a lot. I post around 6 articles per day, of around 500 words each, on average. So what’s that? 3k words per day, 15k words per week? Something like that.

Here’s how I go about it:

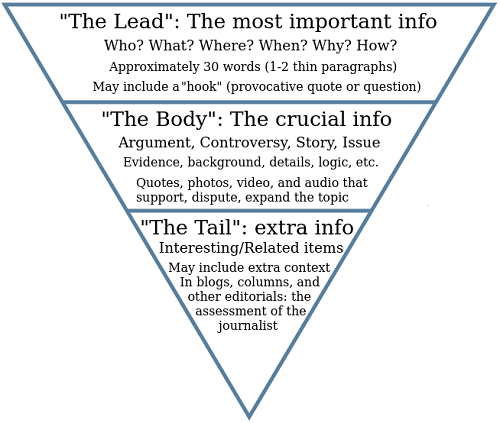

- My approach to non-fiction work is built on the inverted pyramid structure, where the most important information comes first, then the rest of the detail trickles down from there. Sometimes I drift in the intro, then I have to go back and rectify this to ensure that the most important stuff is at the beginning.

- The structure of my posts for SMT is basically ‘what the change is,’ ‘how it works,’ and ‘why it matters to our readers.’ The last element is important, because it’s that extra analysis that differentiates the content.

- I don’t waste time worrying about how to approach a topic, I just start writing. Most of the time, because I’ve done it so often, that ends up being the structure I go with, but I sometimes have to revise to ensure it flows correctly, while I also sometimes change focus in writing the piece, based on additional research. Then I need to go back and ensure the focus is consistent throughout.

- Fact-checking is obviously critical, and sometimes that requires a fair bit of technical understanding, especially for more complex changes and updates. So some posts take longer to create than others because I might need to get my head around some programming language or complex ad targeting approach. As a result, the time it takes to write a piece is relative to the content, not the length

- I maintain contacts at all the platforms I write about in order to double check questionable stories or info

- I don’t write with SEO in mind, necessarily, as the relevant references will be included in the post info, and Google’s systems are very good at understanding context. I do write custom URLs with SEO in mind

- Clarity is king. If I can simplify or shorten the language, I’ll go with that, but when I’m re-reading the post before submitting, I’ll ensure that I don’t get caught on any sentences, and add in explanatory verbs to clarify.

Non-fiction is more formulaic, and there are style notes and approaches that relative to each publication, which will help guide your approach

But I think the main thing is to write something as you would explain it to somebody, someone who might not have the same technical knowledge or understanding of the topic or industry. If you can do that, in an interesting way, while also noting relevant details that others might miss, that’s the best way to approach non-fiction writing.

There are also approaches for interviews and longer reports that are based on the specifics of what you’re doing with each. But as always, clarity and accuracy are key.

Clarity builds relationships with readers, accuracy builds trust. And over time, that’s how you grow your audience.