Tagged: Non-Fiction

non-fiction

For my day job, I write non-fiction, as the head of content for Social Media Today, which is an industry publication for digital marketers.

For a long time, I’d avoided writing for a day job, due to the concern that if I was writing all day, I wouldn’t want to write at night, on my fiction projects. But that conflict has never really been an issue, as I’ve been just as productive, if not more, since taking on a writing job.

And I do enjoy it. I like thinking about the cultural and societal impacts of evolving technologies, and how they change the way we interact, and social media is at the center of this, driving all-new trends and behaviors.

But non-fiction writing is also much different, and the approach to non-fiction requires a different mindset, where you’re less focused on cadence, and more focused on clarity.

I don’t have any hard and fast rules for how I approach journalism, just notes based on traditional journalistic structure and what I’ve learned over time.

And I write a lot. I post around 6 articles per day, of around 500 words each, on average. So what’s that? 3k words per day, 15k words per week? Something like that.

Here’s how I go about it:

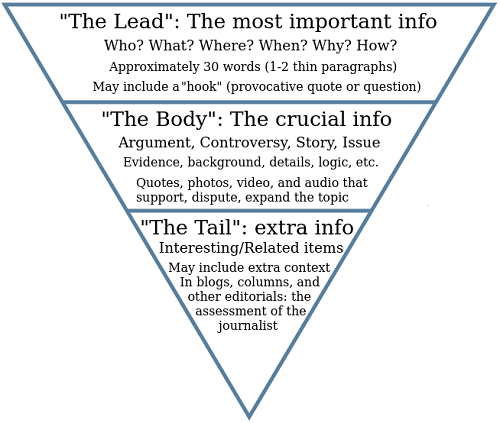

- My approach to non-fiction work is built on the inverted pyramid structure, where the most important information comes first, then the rest of the detail trickles down from there. Sometimes I drift in the intro, then I have to go back and rectify this to ensure that the most important stuff is at the beginning.

- The structure of my posts for SMT is basically ‘what the change is,’ ‘how it works,’ and ‘why it matters to our readers.’ The last element is important, because it’s that extra analysis that differentiates the content.

- I don’t waste time worrying about how to approach a topic, I just start writing. Most of the time, because I’ve done it so often, that ends up being the structure I go with, but I sometimes have to revise to ensure it flows correctly, while I also sometimes change focus in writing the piece, based on additional research. Then I need to go back and ensure the focus is consistent throughout.

- Fact-checking is obviously critical, and sometimes that requires a fair bit of technical understanding, especially for more complex changes and updates. So some posts take longer to create than others because I might need to get my head around some programming language or complex ad targeting approach. As a result, the time it takes to write a piece is relative to the content, not the length

- I maintain contacts at all the platforms I write about in order to double check questionable stories or info

- I don’t write with SEO in mind, necessarily, as the relevant references will be included in the post info, and Google’s systems are very good at understanding context. I do write custom URLs with SEO in mind

- Clarity is king. If I can simplify or shorten the language, I’ll go with that, but when I’m re-reading the post before submitting, I’ll ensure that I don’t get caught on any sentences, and add in explanatory verbs to clarify.

Non-fiction is more formulaic, and there are style notes and approaches that relative to each publication, which will help guide your approach

But I think the main thing is to write something as you would explain it to somebody, someone who might not have the same technical knowledge or understanding of the topic or industry. If you can do that, in an interesting way, while also noting relevant details that others might miss, that’s the best way to approach non-fiction writing.

There are also approaches for interviews and longer reports that are based on the specifics of what you’re doing with each. But as always, clarity and accuracy are key.

Clarity builds relationships with readers, accuracy builds trust. And over time, that’s how you grow your audience.

What We Didn’t Know

I’m always writing. I write 1000 words a day – but I aim for 3000 – and that’s spread across various articles, fiction, specific projects, etc. Some of these turn into posts or stories, some become larger projects and then others, they sit. I submit to different places, save things I’ll come back to later, but sometimes pieces come together and I don’t have a home for them. But I have to write them – really, I have such a compulsion to write that it eats at me if I don’t get them all out. With that, I thought I might start posting some of those pieces here. Short essays, fiction, things that I really like but that don’t necessarily fit anywhere specific. Today, I went to see Ben Watt speak at the Melbourne Writers’ Festival, and he was great. He was talking about his new book, a memoir of his family life, or more, his parents’ relationship, and when I got home, I was inspired. I thought maybe I’d have a go at it – I’m obviously not as high-profile as Ben Watt, and my life isn’t as interesting. But the way he wrote, the beautiful way he presented parts of his life, it fascinated me. So here’s a short, non-fiction piece about my Dad. Hope you like it.

My Dad would change the channel when those road safety awareness ads came one. You know the ones, with the graphic depictions of car accidents, shoulder blades splashing into windscreens. There was this one where there was a kid on a road and a car sped through and trampled him, tumbling his body beneath. My Dad couldn’t watch that one, the images too painful in his head, memories he could smell, feel. We didn’t know, we were just kids. We didn’t understand. So what if some kid gets run over by a car on TV, it’s not real, right? But Dad had seen it for real, he’d been there when it happened. Held bloody hands as warmth faded from them. He knew those scenes more than anyone should.

He was an ambulance officer, my Dad, but before that, he’d served in Vietnam, a career history that my brother and I cherished as kids. He had models of army helicopters and remainders of ration packs in drawers and Dad had pictures of himself with machine guns and riding in helicopters, looking down onto the jungle. Dad was a hero, a real life army man who then went on to save lives in the ambulance. I remember times when our weekend trips would be halted, my brother and I strapped in our seats, waiting by the roadside because Dad had stopped to help at some accident. We played with GI Joes when we were kids, we idolised those characters. Those were my Dad. That’s what he did. That’s what we knew.

When he started to show the effects we didn’t understand. He’d be angry for no reason, upset and we didn’t know why. He started switching the channel away from those ads and we’d be like ‘what are you doing?’ and he never wanted to say and he’d clench his teeth then leave the room. Mum would tell us Dad doesn’t like those ads. Then things got really bad. I remember Dad sitting on the floor in the kitchen, his head low, back against the laundry door. He had a carving knife in his hand. We didn’t understand, but Dad had taken on one thing too many, seen more than anyone ever should. And he couldn’t take anymore.

Eventually he got help. He talked to people and he stopped work and he got a returned services pension. He’s still damaged, still broken, but he’s okay. And he’s still a hero to me, someone who’s done amazing things, things of great pride. But what we didn’t know is that heroes are human too. Everyone has a breaking point, you can only numb yourself to so much. Sometimes I see him, when he doesn’t know I’m watching, and he’s just looking at his hands.

And I remember that one time, when I came home from school after bragging to my friends about my Dad, how he was in the Army and a soldier and I came home to him, an eight year-old kid, and I stood in front of him and said: ‘Dad, have you ever killed anyone?’

Because we didn’t know.