Tagged: Writing tips

non-fiction

For my day job, I write non-fiction, as the head of content for Social Media Today, which is an industry publication for digital marketers.

For a long time, I’d avoided writing for a day job, due to the concern that if I was writing all day, I wouldn’t want to write at night, on my fiction projects. But that conflict has never really been an issue, as I’ve been just as productive, if not more, since taking on a writing job.

And I do enjoy it. I like thinking about the cultural and societal impacts of evolving technologies, and how they change the way we interact, and social media is at the center of this, driving all-new trends and behaviors.

But non-fiction writing is also much different, and the approach to non-fiction requires a different mindset, where you’re less focused on cadence, and more focused on clarity.

I don’t have any hard and fast rules for how I approach journalism, just notes based on traditional journalistic structure and what I’ve learned over time.

And I write a lot. I post around 6 articles per day, of around 500 words each, on average. So what’s that? 3k words per day, 15k words per week? Something like that.

Here’s how I go about it:

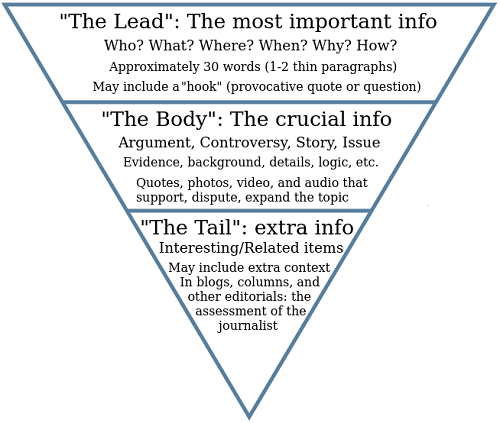

- My approach to non-fiction work is built on the inverted pyramid structure, where the most important information comes first, then the rest of the detail trickles down from there. Sometimes I drift in the intro, then I have to go back and rectify this to ensure that the most important stuff is at the beginning.

- The structure of my posts for SMT is basically ‘what the change is,’ ‘how it works,’ and ‘why it matters to our readers.’ The last element is important, because it’s that extra analysis that differentiates the content.

- I don’t waste time worrying about how to approach a topic, I just start writing. Most of the time, because I’ve done it so often, that ends up being the structure I go with, but I sometimes have to revise to ensure it flows correctly, while I also sometimes change focus in writing the piece, based on additional research. Then I need to go back and ensure the focus is consistent throughout.

- Fact-checking is obviously critical, and sometimes that requires a fair bit of technical understanding, especially for more complex changes and updates. So some posts take longer to create than others because I might need to get my head around some programming language or complex ad targeting approach. As a result, the time it takes to write a piece is relative to the content, not the length

- I maintain contacts at all the platforms I write about in order to double check questionable stories or info

- I don’t write with SEO in mind, necessarily, as the relevant references will be included in the post info, and Google’s systems are very good at understanding context. I do write custom URLs with SEO in mind

- Clarity is king. If I can simplify or shorten the language, I’ll go with that, but when I’m re-reading the post before submitting, I’ll ensure that I don’t get caught on any sentences, and add in explanatory verbs to clarify.

Non-fiction is more formulaic, and there are style notes and approaches that relative to each publication, which will help guide your approach

But I think the main thing is to write something as you would explain it to somebody, someone who might not have the same technical knowledge or understanding of the topic or industry. If you can do that, in an interesting way, while also noting relevant details that others might miss, that’s the best way to approach non-fiction writing.

There are also approaches for interviews and longer reports that are based on the specifics of what you’re doing with each. But as always, clarity and accuracy are key.

Clarity builds relationships with readers, accuracy builds trust. And over time, that’s how you grow your audience.

story vocabulary

The challenge of great writing is that it’s more than the story and the characters that populate it. It’s the writing, the specific language that you use, the pacing and sentence structure. It’s ideation, alliteration, and the vocabulary of this particular narrative.

Which is important to specify. Each story has its own voice, its own way of speaking, which may not be your voice, necessarily, but the one that’s best suited to communicate this tale.

Great writing has a grasp of the tone and meaning of each word, each sentence, and the punctuation within it, to ensure that it remains true to the perspective through which we’re viewing it.

Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” is a great example, a story that’s similar to McCarthy’s other works, but the language is more stark, evoking the bleak poetry of the end of days.

The language is as much a part of the story as the content itself, and it’s important to note the metaphors being used, the words and where they’re placed, and how they relate to the emotion that McCarthy is trying to evoke at any given time.

The same applies to your own work. Does the imagery of your language match the tenor of the scene? Should you be using shorter sentences to pick up the pace, or longer ones to draw out the emotion?

The rhythm and flow of your writing needs to press the emotional buttons that you’re working towards, and each element, every sentence, comma and verb, either builds upon this, or it doesn’t.

literary theory

I’m always slightly offended when people claim that they can see what I was ‘trying’ to do with a story or character, or when they imply that I’ve replicated this or that literary device, mostly based on incorrect assumptions.

I mean, some of those comparisons are positive, which can be a compliment, I guess. But often, the suggestion seems to be that I don’t know about literary theory, that I don’t understand the machinations of story, and that maybe I’ve just read a few pop-culture novels and tried my hand at the same.

Make no mistake, it’s incumbent on any writer to do their research, and to understand the writers that have established the foundations of literature, so that they can then apply, and even bend the rules as they see fit.

This is one of the main reasons that I’ve always been hesitant to try crime fiction, or a fantasy story, because I need to have read widely within a genre to be able to competently create within that space. And while you might be able to add a different take, I think you do need to know the building blocks of any story or creative type, at least in basic form, in order to be able to maximize your creativity. Otherwise you may well be headed towards replication and cliché, without even knowing it.

If you haven’t read Shakespeare or Hemingway, you definitely should at least delve into each a little, and get a sense for what was so great about them. The same for all the classics in whatever genre you want to write, you should be able to analyze and assess some of the key writing elements of the greats, and get a feel for how their stories tick.

You should understand the difference between narrative styles, and writing styles as well. You should be able to identify minimalist writing, and understand the nuance of exposition within the context and style of a bigger narrative.

And definitely, you need to have a grasp of The Hero’s Journey, which is the foundational pathway for every story throughout time.

Understanding how stories have been communicated, and the common elements that contribute to a satisfactory narrative, in alignment with how we all understand such, is key to ensuring that your narrative touches on all the emotional pay-offs, and feels complete.

It’s the key formula, if you want to call it that, of fiction, and if you don’t understand it instinctively, it’ll show throughout your work.

Every story that you’ve ever loved aligns with Joseph Campbell’s research into narrative structure, and once you see it, story writing will make a whole lot more sense.

storytellers

I once heard a very famous novelist refute the ‘show don’t tell’ writing mantra by explaining that:

‘We’re storytellers, not story showers.’

My initial reaction was that I wanted to physically fight him, this man who’s sold many, many books, but whose writing I do not respect.

Because show don’t tell is a critical tenet for great writing, because without it, then you’re more of a story planner than a writer. And that is a challenge in itself, don’t get me wrong. But it’s like the difference between someone who explains what they want to paint, and somebody who can actually bring it to life.

Great writing requires color, shading, attention to detail, and not just in the details of scene itself, but in the words that you use to illustrate such. Understanding the difference between showing and telling is the difference between making your audience comprehend your story, and feel it. And in some genres and styles, that’s fine. People who read thrillers are looking for fast-paced action, and they’re not as interested in reading a challenging narrative about the conflicting emotions of the main character. So you can succeed in telling not showing in that context, though I would still argue that you need to understand the principle, in order to apply or ignore it at will.

Stories that tell more than show will fail to resonate as much as they could, and won’t be as captivating, or emotionally involving as great writing. You want to recreate the scene in your head, and not just what’s happening, but the detail that the characters would notice, the expanded physical cues that point to how the people or creatures within it are feeling. It’s those elements that are the real gold, the real resonators that elevate a story to another level.

You can argue against this if you want, but you’ll be wrong. And the more that you dig into the emotions and responses, beyond the core story elements, the better your writing will be.

safe distance

I’m gonna be honest, I dislike Stephen King’s writing. I understand that he’s the originator of many elements that have defined generations of writers after him, and I don’t mind the creativity of his stories. But his writing style is not for me.

But I did find his “On Writing” book interesting, and in particular, his notes about creation, and leaving your work to sit in a drawer for at least six weeks after you’ve completed a revised first draft.

As per King:

“[After six weeks] take your manuscript out of the drawer. If it looks like an alien relic bought at a junk-shop or a yard sale where you can hardly remember stopping, you’re ready. Sit down with your door shut, a pencil in your hand, and a legal pad by your side. Then read your manuscript over.”

The idea is that this creates enough distance from the passion that you had in that first draft stage to enable more objectivity in your re-reading, which will then better enable you to see errors and issues that you may have been too attached to acknowledge otherwise.

The more your story reads like someone else wrote it, the better. And ideally, that someone else, you find, is actually a good writer, and has come up with some sequences that impress you.

Which can give you some encouragement, while also enabling you to review your work with a more critical, analytical eye.

And sure, that might also mean that you read some parts that hurt your head as you try understand what the heck you were thinking.

But if you know this, if you notice issues, if you get slowed in your reading process, if you get bored, chances are that your audience will as well.

Forcing a level of distance from your work will improve your assessment, and ultimately your writing as a result.

word processing

I’ve heard a range of writers, both successful and not, espousing the virtues of different word processing tools and creative processes.

Maybe you find Word annoying, maybe you get comfort from an old typewriter, maybe there’s something about the physical process of writing by hand that helps you get more ideas down in a more coherent manner.

Whatever approach you use, the only thing I would advise is to not get too caught up in the how, and maintain focus on the actual work, including research, structure, revision, editing.

Because some people get too involved in which process you use.

“Do you use Word? That’s crazy. I write on a 1954 typewriter in the dark, so I can’t see what I’ve written till I’m finished.”

Yeah, that’s just stupid, and the reality is it doesn’t matter. What works for you, works for you, and you don’t need to worry about what process you use, nor how it’ll be judged.

Word is fine. WordPad is fine.

I once challenged myself to write an entire novel in the Notes app on my phone, and that was also fine.

Some apps are different, some tools feel more at home. But there’s no need to get too caught up on the how.

Just do what you do.

therefore

South Park writers Matt Parker and Trey Stone recently shared their story-writing advice, in simplified form, which provides a valuable mechanism for ensuring cohesion in your story.

The basic approach, as outlined by Parker and Stone, is this:

When you have a set of story beats or scenes, you can ensure that they’re interconnected, and helping to build your story, by imagining the terms ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ between them. If the story makes sense, ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ will be the logical connectors, ensuring that there’s a logical sequence to your narrative, as opposed to ‘and then,’ which could indicate a disconnect, in that the scenes don’t necessarily relate to one another.

Essentially, this means that the story is evolving based on what’s come before it, and what the audience already knows, as opposed to you injecting disconnected or subsidiary elements.

So, let’s take Star Wars, for example. In “A New Hope,” the connection between the opening scenes would be:

‘Darth Vader attacks Rebel ship’

Therefore

‘Princess Leila puts the message to Obi Wan in R2 and sends him off to an escape pod’

Therefore

‘The robots end up on Tattooine’

But

‘That’s also where Luke Skywalker lives’

So you’re connecting the story in logical sequence, as opposed to ‘and then’ which is not necessarily consequential of the preceding element.

An example of an ‘and then’ here might be a cut between these scenes to Han Solo and Chewbacca running a smuggling job. It’s possible that this may be another story element of note, but it wouldn’t build upon what’s come before it, and might therefore feel disjointed and out of place.

The approach helps to ensure that your story gathers momentum based on each event, as opposed to losing focus through side-stories or unrelated narratives.

The concept reminded me of Gordon Lish’s writing advice, which is more specific to writing structure than scene building, but follows the same line of thinking.

Lish is a renowned editor, who reportedly made many of Raymond Carver’s stories what they were through his meticulous approach to sentences, and merciless editing. Lish was also a longtime writing teacher, and has helped many authors refine their literary voice.

And as noted, Lish’s approach to the fiction writing process bears similar notes to the South Park writers’ notes.

As summarized by Christine Schutt, an author who’s worked with Lish:

“Each sentence is extruded from the previous sentence; look behind when you are writing, not ahead. Your obligation is to know your objects and to steadily, inexorably darken and deepen them. Query the preceding sentence for what might most profitably be used in composing the next sentence. The sentence that follows is always in response to the sentence that came before.”

Lish also taught repetition and the recalling of details and objects to color your stories, with the first sentence of your work acting as an ‘attack sentence.’

“Your attack sentence is a provoking sentence. You follow it with a series of provoking sentences.”

The idea is that this builds the story block by block, engaging the reader by expanding on the theme with more and more exploratory sentences.

The sequencing of such is similar to using the ‘therefore’ and ‘but’ approach to keep things tethered to your main concept, though Lish’s notes are more stylistic and designed to help in your actual communication of your story.

But there’s a linkage there, which could help to keep your writing compelling and accumulating over time, driving readers towards your peaks.

(Note: Another of Lish’s writing tips I like is ‘stay on the body,’ and don’t go below the surface of your objects, seeking to explain their inner truths. Lish’s view is that you should rely on your descriptions to guide emotional response in your readers, and giving away too much in blatant exposition on this front will blunt your writing.)

To be clear, there’s no foolproof strategy to creative writing, but both concepts provide some additional food for thought as to how you might go about creating more compelling, engaging work.

Jesse Ball

I find Jesse Ball’s writing process fascinating, though I doubt I could ever recreate it myself.

Jesse Ball has written nine novels, and various shorter works, which have been both lavished and criticized within certain literary circles. Not that he seems to care about such either way, because the way Ball sees it, creating a novel is a performance, and like any other form of performance art, the result is based on whatever factors were present at the exact time and place in which it was written.

Maybe it’s good, maybe it’s bad, but his writing process is very short, and built upon meticulous preparation, as opposed to most writers who focus on editing and revision.

Indeed, Ball says that the typical writing process for his novels takes place over 4-14 days.

Note, that’s “days” not “weeks” or “months.”

Ball schedules a writing period, when he’s away from his day-to-day life, then he goes on, essentially, a writing sprint, and completes his novels in these comparatively short bursts.

Which is a very deliberate choice.

As per Ball:

“I want to take the least amount of time possible. I want to be deliberate. I don’t want to take any missteps. I want to have a genuine technique that allows the things that I say to be clearly said and I want to say them in the order in which they are meant to be said, to most clearly elucidate the idea. The reader should be able take the same path that I took.”

Ball’s view is that the writer and reader should be as closely aligned as possible in experiencing the story, and while he’s also committed to reading and researching in preparation for such, the actual writing process, in his view, should not be drawn out. So it’s writing as an in-the-moment performance.

“I don’t edit – I think the original form is best. Sometimes [my editor] will ask me for more, and then I will add a section.”

Yeah, it’s pretty hard to imagine that many writers would be able to get away with the same, and produce anything of publishable quality within a matter of days. But again, Ball says that this is a failure of preparation, not of the writing process itself, and that the right steps to establish the project in your mind will enable you to create a fresh and cohesive narrative based on such sprints.

I would guess that most writers would have trouble even putting down 70k words in two weeks, but there is a logic to his thinking, and I definitely respect his commitment to such process.

And maybe it’s worth considering, that rather than trying to push through writing 1k words a day, maybe you should spend more time on planning and research, then aim to have more free-flowing writing sessions in focussed sprints.

Either way, it’s another process to consider (particularly for National Novel Writing Month)

the tiktok-ificiation of creativity

I read an interesting quote recently, which apparently came from the Russo brothers, who are currently developing the new Avengers films for Marvel.

As per Joe Russo:

“We are designing a movie specifically for the TikTok audience. Embracing the low attention spans will save the industry.”

I haven’t been able to verify 100% that this came from Joe Russo, but it wouldn’t be the first time the Russo brothers have talked about this approach.

When developing a live-action Hercules series back in 2022, they also noted that they would be looking to better align with the TikTok generation, explaining that:

“[Young viewers] don’t have the same emotional connection to watching things in a theater.”

But what does that mean, exactly? If younger audiences don’t align with storytelling in the same way, what does that mean for film, and storytelling in general, and how can we learn from that, as writers, to maximize the appeal of our work?

I think we might have actually seen it in practice in the new ‘Superman’ movie. For those who are unaware, James Gunn’s reimagining of Superman, his first film as the head of the new DC Studios cinematic universe, is super fast-paced, giving limited time to character development, and maximum time to cartoonish, crazy action sequences.

The approach, basically, is that the audience already knows the Superman story. You already know about the kid from Krypton who crashed on Earth and was raised by farmers, and gradually learned that he’s different, etc. We all know this, so Gunn has wasted no time on that element, choosing to start the movie 3 years after Superman has risen to public consciousness.

Which also means that Superman is already in a relationship with Lois Lane, and that Lex Luthor hates Superman. Also, Supergirl exists.

We don’t have any specific context for the relationships between these characters, but the idea, seemingly, is that we don’t need it. You just get in, fill in the blanks, and enjoy the ride.

Except, there’s literally no emotional payoff in that approach. We, as the audience, don’t feel anything for Lois Lane and Clark Kent as a couple, because we don’t see them build their connection over time. We have no context for exactly why Lex Luthor, personally, hates Superman so much. And without that emotional connection, the film is just like a music video, a series of flashy scenes, that are fine as action sequences, but feel more like a couple of hours of scrolling through TikTok, with not much really sticking in mind, and connecting with your emotional reasoning.

That, to me at least, seems like a far less resonant storytelling approach. But again, as the Russos note, maybe that’s the point, because young viewers don’t have the same emotional connection with movies anyway.

But it feels like a step back. In large part, it feels like a commercial push, a promo reel of footage to sell action figures, and not much else.

Sure, I can fill in the blanks, I can assume the connections, and follow along with the story. But I don’t have any connection to it, and that, I would suggest, is not the way that you want to go with your stories.

And I don’t believe that’s what modern audiences want. ‘Stranger Things,’ for example, spends significant time on character development, and establishing emotional connection between the characters. ‘The Last of Us’ does as well. These are massive commercial hits, that still focus on story versus action.

Because without those connectors, the action doesn’t mean as much, and I don’t accept that the TikTok generation is somehow evolving beyond thousands of years of storytelling as a core element of our being.

what does good writing mean in 2025?

This is a question that I’ve considered a lot – is good writing the peak of literary form, as in the construction of beautiful sentences, the creation of vivid worlds, the expression of emotion within paragraphs, all based on honed skill? Or is good writing what sells, and thus, defined more by what grabs attention and holds it? Which, based on modern sales numbers, would be more cliche, action romance-style content?

Because to me, great writing is writing that conveys real emotion. Great authors are able to recreate the emotional sense of the scene that they’ve imagined within the body of the reader, making reading a novel the closest thing we have to viewing the world through the eyes of somebody else. The setting, the concept, the idea that you’re exploring, all of this needs to be exuded through the words that you choose, and the specific placement of each verb needs to add to the broader picture, and draw out the emotion of each scene.

This is the pursuit of all great writers, and yet, I would argue that some of the best writers on this front likely wouldn’t sell many copies in the current literary landscape.

Does that mean that this is no longer ‘good’ writing? Is good writing defined by the market? By the readers? Or is good writing based on the sense that the writer gets from creating it?

It’s hard to define, and success, of course, is relative. I once wrote a kids’ book series for my own children, with the idea being that it would expand upon literary concepts and mechanisms as each book went on. So by the third book, we have more metaphor, while the first is more expository and flat. The idea, in my head at least, was that this would open their eyes to literary and storytelling devices, and that would help them create better stories of their own.

Maybe that worked, but then again, if other readers don’t have the same understanding, does that even matter?

If you want to sell books, then more straightforward, escapist stories are doing better right now. The reading public has less time to commit to a novel, so they’re more likely, seemingly, to engage with books that go from point-to-point, in quick succession, with driving, fast-paced narratives that don’t require a lot of considered thought.

This is a generalisation, of course, as there are still some novels that gain traction that do require more analysis and questioning. But I’ve literally been told by some within the publishing industry that as a middle-aged male author, I need to be concentrating on thrillers and fast-paced stories, as opposed to literary fiction.

Because that’s what sells, and as such, should those teaching writing courses be focused on what would be considered good, artistic writing that explores the virtues of the characters, and encourages deeper thought, or should we all sign up for the next action thriller workshop, and concentrate on reimagining James Bond stories in modern settings?

I don’t know the answer, but I can tell you that many great literary works are sitting on hard drives, never to be read, because the market is just not interested in them at present.

And maybe, with short-form video swallowing up all of our leftover attention spans, there’s no way back for more considered, literary works.