Tagged: Creativity

literary theory

I’m always slightly offended when people claim that they can see what I was ‘trying’ to do with a story or character, or when they imply that I’ve replicated this or that literary device, mostly based on incorrect assumptions.

I mean, some of those comparisons are positive, which can be a compliment, I guess. But often, the suggestion seems to be that I don’t know about literary theory, that I don’t understand the machinations of story, and that maybe I’ve just read a few pop-culture novels and tried my hand at the same.

Make no mistake, it’s incumbent on any writer to do their research, and to understand the writers that have established the foundations of literature, so that they can then apply, and even bend the rules as they see fit.

This is one of the main reasons that I’ve always been hesitant to try crime fiction, or a fantasy story, because I need to have read widely within a genre to be able to competently create within that space. And while you might be able to add a different take, I think you do need to know the building blocks of any story or creative type, at least in basic form, in order to be able to maximize your creativity. Otherwise you may well be headed towards replication and cliché, without even knowing it.

If you haven’t read Shakespeare or Hemingway, you definitely should at least delve into each a little, and get a sense for what was so great about them. The same for all the classics in whatever genre you want to write, you should be able to analyze and assess some of the key writing elements of the greats, and get a feel for how their stories tick.

You should understand the difference between narrative styles, and writing styles as well. You should be able to identify minimalist writing, and understand the nuance of exposition within the context and style of a bigger narrative.

And definitely, you need to have a grasp of The Hero’s Journey, which is the foundational pathway for every story throughout time.

Understanding how stories have been communicated, and the common elements that contribute to a satisfactory narrative, in alignment with how we all understand such, is key to ensuring that your narrative touches on all the emotional pay-offs, and feels complete.

It’s the key formula, if you want to call it that, of fiction, and if you don’t understand it instinctively, it’ll show throughout your work.

Every story that you’ve ever loved aligns with Joseph Campbell’s research into narrative structure, and once you see it, story writing will make a whole lot more sense.

storytellers

I once heard a very famous novelist refute the ‘show don’t tell’ writing mantra by explaining that:

‘We’re storytellers, not story showers.’

My initial reaction was that I wanted to physically fight him, this man who’s sold many, many books, but whose writing I do not respect.

Because show don’t tell is a critical tenet for great writing, because without it, then you’re more of a story planner than a writer. And that is a challenge in itself, don’t get me wrong. But it’s like the difference between someone who explains what they want to paint, and somebody who can actually bring it to life.

Great writing requires color, shading, attention to detail, and not just in the details of scene itself, but in the words that you use to illustrate such. Understanding the difference between showing and telling is the difference between making your audience comprehend your story, and feel it. And in some genres and styles, that’s fine. People who read thrillers are looking for fast-paced action, and they’re not as interested in reading a challenging narrative about the conflicting emotions of the main character. So you can succeed in telling not showing in that context, though I would still argue that you need to understand the principle, in order to apply or ignore it at will.

Stories that tell more than show will fail to resonate as much as they could, and won’t be as captivating, or emotionally involving as great writing. You want to recreate the scene in your head, and not just what’s happening, but the detail that the characters would notice, the expanded physical cues that point to how the people or creatures within it are feeling. It’s those elements that are the real gold, the real resonators that elevate a story to another level.

You can argue against this if you want, but you’ll be wrong. And the more that you dig into the emotions and responses, beyond the core story elements, the better your writing will be.

safe distance

I’m gonna be honest, I dislike Stephen King’s writing. I understand that he’s the originator of many elements that have defined generations of writers after him, and I don’t mind the creativity of his stories. But his writing style is not for me.

But I did find his “On Writing” book interesting, and in particular, his notes about creation, and leaving your work to sit in a drawer for at least six weeks after you’ve completed a revised first draft.

As per King:

“[After six weeks] take your manuscript out of the drawer. If it looks like an alien relic bought at a junk-shop or a yard sale where you can hardly remember stopping, you’re ready. Sit down with your door shut, a pencil in your hand, and a legal pad by your side. Then read your manuscript over.”

The idea is that this creates enough distance from the passion that you had in that first draft stage to enable more objectivity in your re-reading, which will then better enable you to see errors and issues that you may have been too attached to acknowledge otherwise.

The more your story reads like someone else wrote it, the better. And ideally, that someone else, you find, is actually a good writer, and has come up with some sequences that impress you.

Which can give you some encouragement, while also enabling you to review your work with a more critical, analytical eye.

And sure, that might also mean that you read some parts that hurt your head as you try understand what the heck you were thinking.

But if you know this, if you notice issues, if you get slowed in your reading process, if you get bored, chances are that your audience will as well.

Forcing a level of distance from your work will improve your assessment, and ultimately your writing as a result.

Jesse Ball

I find Jesse Ball’s writing process fascinating, though I doubt I could ever recreate it myself.

Jesse Ball has written nine novels, and various shorter works, which have been both lavished and criticized within certain literary circles. Not that he seems to care about such either way, because the way Ball sees it, creating a novel is a performance, and like any other form of performance art, the result is based on whatever factors were present at the exact time and place in which it was written.

Maybe it’s good, maybe it’s bad, but his writing process is very short, and built upon meticulous preparation, as opposed to most writers who focus on editing and revision.

Indeed, Ball says that the typical writing process for his novels takes place over 4-14 days.

Note, that’s “days” not “weeks” or “months.”

Ball schedules a writing period, when he’s away from his day-to-day life, then he goes on, essentially, a writing sprint, and completes his novels in these comparatively short bursts.

Which is a very deliberate choice.

As per Ball:

“I want to take the least amount of time possible. I want to be deliberate. I don’t want to take any missteps. I want to have a genuine technique that allows the things that I say to be clearly said and I want to say them in the order in which they are meant to be said, to most clearly elucidate the idea. The reader should be able take the same path that I took.”

Ball’s view is that the writer and reader should be as closely aligned as possible in experiencing the story, and while he’s also committed to reading and researching in preparation for such, the actual writing process, in his view, should not be drawn out. So it’s writing as an in-the-moment performance.

“I don’t edit – I think the original form is best. Sometimes [my editor] will ask me for more, and then I will add a section.”

Yeah, it’s pretty hard to imagine that many writers would be able to get away with the same, and produce anything of publishable quality within a matter of days. But again, Ball says that this is a failure of preparation, not of the writing process itself, and that the right steps to establish the project in your mind will enable you to create a fresh and cohesive narrative based on such sprints.

I would guess that most writers would have trouble even putting down 70k words in two weeks, but there is a logic to his thinking, and I definitely respect his commitment to such process.

And maybe it’s worth considering, that rather than trying to push through writing 1k words a day, maybe you should spend more time on planning and research, then aim to have more free-flowing writing sessions in focussed sprints.

Either way, it’s another process to consider (particularly for National Novel Writing Month)

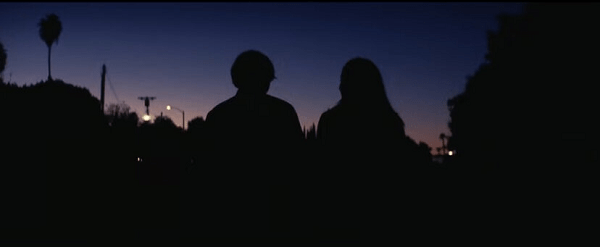

Paul Thomas Anderson

I’ve been rewatching Paul Thomas Anderson’s films of late, as a reminder of what’s so great about them. And all of them have amazing moments. He has that knack for capturing lightning in a bottle, as it were, a capacity to find that hum between ideas and communicating them, where it just hits right and taps into your emotions.

Of course, this is also a personal thing, and many people would get that goosebumps-type feeling from a broad range of books, movies and TV shows. Some characters and scenes and songs will always awaken past memories and familiarity, and it just feels like you’re at one with it, even if for just a moment.

Paul Thomas Anderson can do this better than most, with all of his films having at least a few sequences and interactions that capture that soul-scratching vibe, those moments where it feels like more than a movie, more than actors interacting on screen. He taps into a deep connection that brings everything into balance in the moment.

Maybe you’ve experienced the same. Here are a few images from of some of my favorite moments from his films.

the tiktok-ificiation of creativity

I read an interesting quote recently, which apparently came from the Russo brothers, who are currently developing the new Avengers films for Marvel.

As per Joe Russo:

“We are designing a movie specifically for the TikTok audience. Embracing the low attention spans will save the industry.”

I haven’t been able to verify 100% that this came from Joe Russo, but it wouldn’t be the first time the Russo brothers have talked about this approach.

When developing a live-action Hercules series back in 2022, they also noted that they would be looking to better align with the TikTok generation, explaining that:

“[Young viewers] don’t have the same emotional connection to watching things in a theater.”

But what does that mean, exactly? If younger audiences don’t align with storytelling in the same way, what does that mean for film, and storytelling in general, and how can we learn from that, as writers, to maximize the appeal of our work?

I think we might have actually seen it in practice in the new ‘Superman’ movie. For those who are unaware, James Gunn’s reimagining of Superman, his first film as the head of the new DC Studios cinematic universe, is super fast-paced, giving limited time to character development, and maximum time to cartoonish, crazy action sequences.

The approach, basically, is that the audience already knows the Superman story. You already know about the kid from Krypton who crashed on Earth and was raised by farmers, and gradually learned that he’s different, etc. We all know this, so Gunn has wasted no time on that element, choosing to start the movie 3 years after Superman has risen to public consciousness.

Which also means that Superman is already in a relationship with Lois Lane, and that Lex Luthor hates Superman. Also, Supergirl exists.

We don’t have any specific context for the relationships between these characters, but the idea, seemingly, is that we don’t need it. You just get in, fill in the blanks, and enjoy the ride.

Except, there’s literally no emotional payoff in that approach. We, as the audience, don’t feel anything for Lois Lane and Clark Kent as a couple, because we don’t see them build their connection over time. We have no context for exactly why Lex Luthor, personally, hates Superman so much. And without that emotional connection, the film is just like a music video, a series of flashy scenes, that are fine as action sequences, but feel more like a couple of hours of scrolling through TikTok, with not much really sticking in mind, and connecting with your emotional reasoning.

That, to me at least, seems like a far less resonant storytelling approach. But again, as the Russos note, maybe that’s the point, because young viewers don’t have the same emotional connection with movies anyway.

But it feels like a step back. In large part, it feels like a commercial push, a promo reel of footage to sell action figures, and not much else.

Sure, I can fill in the blanks, I can assume the connections, and follow along with the story. But I don’t have any connection to it, and that, I would suggest, is not the way that you want to go with your stories.

And I don’t believe that’s what modern audiences want. ‘Stranger Things,’ for example, spends significant time on character development, and establishing emotional connection between the characters. ‘The Last of Us’ does as well. These are massive commercial hits, that still focus on story versus action.

Because without those connectors, the action doesn’t mean as much, and I don’t accept that the TikTok generation is somehow evolving beyond thousands of years of storytelling as a core element of our being.

what does good writing mean in 2025?

This is a question that I’ve considered a lot – is good writing the peak of literary form, as in the construction of beautiful sentences, the creation of vivid worlds, the expression of emotion within paragraphs, all based on honed skill? Or is good writing what sells, and thus, defined more by what grabs attention and holds it? Which, based on modern sales numbers, would be more cliche, action romance-style content?

Because to me, great writing is writing that conveys real emotion. Great authors are able to recreate the emotional sense of the scene that they’ve imagined within the body of the reader, making reading a novel the closest thing we have to viewing the world through the eyes of somebody else. The setting, the concept, the idea that you’re exploring, all of this needs to be exuded through the words that you choose, and the specific placement of each verb needs to add to the broader picture, and draw out the emotion of each scene.

This is the pursuit of all great writers, and yet, I would argue that some of the best writers on this front likely wouldn’t sell many copies in the current literary landscape.

Does that mean that this is no longer ‘good’ writing? Is good writing defined by the market? By the readers? Or is good writing based on the sense that the writer gets from creating it?

It’s hard to define, and success, of course, is relative. I once wrote a kids’ book series for my own children, with the idea being that it would expand upon literary concepts and mechanisms as each book went on. So by the third book, we have more metaphor, while the first is more expository and flat. The idea, in my head at least, was that this would open their eyes to literary and storytelling devices, and that would help them create better stories of their own.

Maybe that worked, but then again, if other readers don’t have the same understanding, does that even matter?

If you want to sell books, then more straightforward, escapist stories are doing better right now. The reading public has less time to commit to a novel, so they’re more likely, seemingly, to engage with books that go from point-to-point, in quick succession, with driving, fast-paced narratives that don’t require a lot of considered thought.

This is a generalisation, of course, as there are still some novels that gain traction that do require more analysis and questioning. But I’ve literally been told by some within the publishing industry that as a middle-aged male author, I need to be concentrating on thrillers and fast-paced stories, as opposed to literary fiction.

Because that’s what sells, and as such, should those teaching writing courses be focused on what would be considered good, artistic writing that explores the virtues of the characters, and encourages deeper thought, or should we all sign up for the next action thriller workshop, and concentrate on reimagining James Bond stories in modern settings?

I don’t know the answer, but I can tell you that many great literary works are sitting on hard drives, never to be read, because the market is just not interested in them at present.

And maybe, with short-form video swallowing up all of our leftover attention spans, there’s no way back for more considered, literary works.

self publishing

Another avenue to consider for writing, and one that’s now become a far more viable option, is self-publishing, and using platforms like Amazon to get your work out there, and into the hands of a reading audience.

And it’s easy to do. I self-published a novel a couple of years back, just to see how difficult it was, what the opportunities may be, etc.

It is pretty simple, and with new elements like AI image generators, creating a good-looking cover, and/or promotional content, is also easier than ever, giving you even more opportunity to create a book product that you can then sell and make money from.

The actual creation process (in terms of the book product, not the writing of the novel itself) is easy. But the real challenge with self-publishing lies in effective promotion, and raising awareness of your work.

Promotion and marketing is difficult in any context, and for most authors, who spend years alone in quiet rooms, plugging away at their novel, it’s pretty intimidating to go from that setting to speaking in front of a radio mic, or a room full of people.

It’s hard to do well, and can be a nerve-wracking experience. But you have to do it, in order to get people aware that you’ve actually written a book. Because if they don’t know, they can’t buy it, right?

Social media has made this a little easier, in that you can run social media ads, targeted to the right readers, while you can also build your own social media presence to help promote your work. But this is also both expensive and time-consuming. And again, it runs counter to the personality type of most writers.

Do you really want to be posting an Instagram Story every day, in order to maintain awareness, when you’d rather be writing?

This is why traditional publishing is a better route, for those that are able to take it, because publishing houses have their own PR teams and media connections that will get that coverage for you. Then you just have to show up and speak. When you’re self-publishing, the chances of you getting anywhere near that coverage is nil, and without that initial step of actual awareness, you’re not going to generate enough sales to make any money from your self-published work.

Which is the prime challenge. Self-publishing is not just creation, it’s promotion, and you need to come up with a plan for how you’re going to get people – many people – aware that you’ve published a new book.

That’s not easy, and without a few thousand dollars in marketing budget, it’s probably not going to be the savior approach that some suggest.

You also have to write something that resonates with an audience, and like traditional publishing shifts, literary fiction is not a big seller for Amazon readers.

On Amazon, for example, romance, fantasy, mystery/thriller, and science fiction sell the best, along with self-help, while ‘romantasy’ is a rising focus. If you’re writing in these genres, then you may have a better opportunity for discovery, and I would recommend checking in with the top sellers, and learning from their success, in order to better inform your approach.

But that also means refining your personal style and approach to align with what works, which may not be how you want to go about it. In which case, you better get happy with selling a few copies to your friends and family, and not much else.

There’s also been much talk about the ‘creator economy,’ and the opportunities of social media and video platforms, which enable anybody to explore their passions and generate income from their work. The only note I would advise on this is that while you do now have more platforms through which to find an audience, 96% of all online creators earn less than $100k per year.

Most people are not making money online, or they’re not making enough to live on, and if you’re dreaming of becoming a full-time writer, the opportunities of self-publishing may not be enough to sustain that goal.

Though it depends on your approach, it depends on your targeting, how flexible you’re willing to be, how good you are at what you do, and how many people you can get to talk about your books.

Maybe, if you reach the right influencers who say the right, positive things about your books, you’ll make some big sales, and you can use that as a platform for larger success.

But then again, self-publishing platforms are also increasingly being flooded with AI-generated content, which is diluting reader trust, and will impact overall sales.

Basically, what I’m saying is that self-publishing, as a process, is easy, but self-promotion, for most writers, is very hard, and getting attention in an increasingly crowded pool of content is challenging.

So if you are going to self-publish, you need to put a lot of focus on your promotional plan, and maybe start by cultivating a targeted social media following, that’s interested in the genre you write in, before you consider publishing.

novel influence

We vastly underrate the value of stories, and the contributions that they make to society.

Creative writing, like all arts, is often seen as an expendable funding element, and among the first option when it comes to, say, funding cuts by government bodies.

“Why should our taxes pay for this guy to sit at home and make up stories?”

I know the arguments, and anyone in any creative industry has felt the impacts of such in action. But this perspective doesn’t account for the transformative power of storytelling, and the ways in which writing, painting, music, and every other form of creative pursuit can influence the way that we live.

Put simply, novels are the closest that you will ever get to experiencing the world through somebody else’s eyes.

On the surface, that may not seem like a major thing, but in all of human history, it’s stories that have changed minds, more than anything else, be it in books, movies, short videos on YouTube, etc.

This is why literature is inherently political, because in the telling of stories from varied perspectives, we highlight how people live, and how they experience the world. And that can then sway opinions on social topics, though at the same time, I don’t believe that art should be overtly political in this respect, with a specific aim of reinforcing a political point, or underlining a topical stance.

Artists have a responsibility to the work itself, and nothing else. You could argue that they also have a responsibility to their readers, in ensuring that they remain true to the world that they’ve created, but I would say that this is part and parcel of the first consideration, that in order to create a resonant art work, you need to remain committed to its creation, and stay true to the parameters within which it exists.

That’s where the truth comes from, in being honest about your characters and the situations that they inhabit, exploring the true nature of the work, then presenting that to an audience. It doesn’t have to be ‘good guys versus bad guys,’ it doesn’t have to showcase a specific perspective. An artist should remain attached to the vision of the work, and explore that with a commitment to sharing the characters’ perspective, no matter what direction that may lead.

By presenting things as they are, whether it’s in fiction, non-fiction, in painting, or anything else, you’re then allowing the reader to engage with another perspective. And from that, they can decide how they feel about it.

And that choice is powerful. Depicting rich aristocrats, for example, doesn’t need to be caricatures and clichés, which is the most obvious choice for a general audience, because an honest depiction of who they are, and how they live, will then inevitably also lead to sharing how they view the world, and why they do what they do.

And the reader can judge that for themself.

This is how art changes minds, and highlights society as it exists.

Even in science fiction, remaining true to the parameters of the world that you’ve created will inevitably lead to parallels that mirror real world thinking. The ‘why’ of the story is the driving force, and we read books to get a better sense of why characters do the things that they do, which is influenced by where they come from, what they’ve seen, and how they’ve been treated.

This is how we learn more about the world around us through books, and in my opinion, no other medium is as immersive in sharing somebody else’s perspective as a novel.

The stories may be made up, but the human center of the best fiction is what will always connect us to it.

what AI can’t do

One of my favorite senitments at the moment is that ‘Hollywood is in trouble’ due to AI, with the suggestion being that AI video generators are soon going to enable a new wave of film creation, that will eventually see all kinds of regular folk building their own cinematic empires, because they can generate Hollywood level animation, or similar, with AI tools.

And definitely, AI tools are improving. Each week, there seems to be a new advance in AI video generation, and yes, at some stage, it does seem entirely feasible that you’ll be able to put together a competent, film-length project based on your idea.

But that’s the thing. Creation itself is only a part of the filmmaking journey, and it’s the writing part, in putting together a narrative that resonates with a wide audience, creating characters that work, scenes that pop, ideas that mesh, that’s not easy. And AI cannot, and will not be able to replicate that.

For example, you’ve likely seen those Pixar-style videos generated by AI tools, with people re-posting them saying things like ‘it’s so over’.

But do you know how long it takes the Pixar team to put together a story for one of their films?

Pixar generally has a team of 10 or more writers, some of the best, most experienced minds in the business, who spend several years on story development before it even gets to the storyboard/production phase.

Pixar, like all Disney projects, uses the Hero’s Journey model as its guiding light, which is a formula extrapolated from ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ monomyth structure, and is based on storytelling approaches that have been developed all throughout human existence.

And again, it takes years for them to develop these stories, using the collective experience of a team of storytellers, in order to come up with a narrative that will hit all the emotional pay-offs to maximize resonance.

AI can’t do that for you, and while AI tools may be able to help you refine a script or idea, or even streamline the conversion of your concept into actual screenplay structure, they won’t be able to polish a poor idea to the point where it’ll become a hit.

As such, even if AI tools are able to fully generate the physical elements of movie, very, very few of the ideas that get churned through these tools are actually going to gain any significant audience.

Of course, some will, and there’s no doubt that AI tools will expand opportunities for creators, by giving more people more ways to showcase their ideas in different formats. But even within that, the same rules of creation will apply, which also means that very, very few projects are going to succeed.

If you want to create resonant stories, you’re better off learning about The Hero’s Journey, and applying that to your concepts, than you would be hoping that AI tools will be able to iron out the problems with your ideas.

Most story ideas are not good, most people who think they have a cool concept for a film haven’t done the research into how to create, and it shows in the final product. I mean, even a lot of films that do make it through to production aren’t that great, and they’ve been checked and okayed by a heap of people.

So while AI tools may give you a practical means to bring your ideas to life, they won’t cover for a lack of storytelling knowledge and/or skill.

You should read this book to learn more about The Hero’s Journey in action.